This is an excpert from my book Johnson, A. (2021). Designing meaning-based interventions for reading. Guildford Press.

It bears repeating: Struggling readers are not homogeneous entities (Allington & McGill-Franzen, 2017). Not all struggling readers who have word identification or fluency deficits have comprehension deficits. Likewise, not all struggling readers who have comprehension deficits have word identification and fluency deficits. This chapter focuses on comprehension.

UNDERSTANDING COMPREHENSION

Let us begin by defining our terms: Comprehension is creating meaning with print. If this seems remarkably similar to the definition of reading put forth in Chapter 3, it is because it is, in fact, the same. To read is to create meaning. Creating meaning is the whole point of reading in the first place.

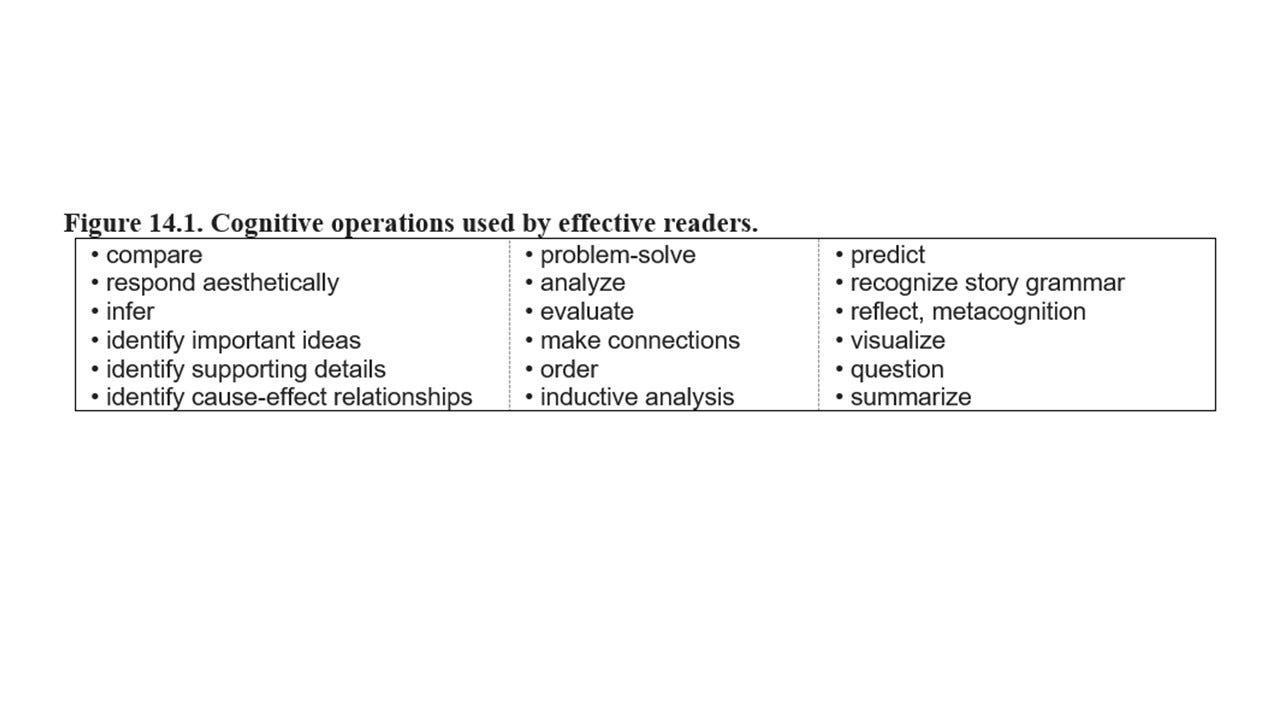

Comprehension is not a passive act. You cannot simply run your eyes over the letters on the page and absorb information. To comprehend, you must be actively engaged at some level with the material being read (Almasi, et.al., 2011; Hoffman, 2017). For example, if you are creating meaning with the text you are currently reading, you are probably doing at least one of the following: (a) checking for understanding, (b) identifying interesting or important ideas, (c) connecting this information to what you already know, (d) pausing every once in a while to see if what you are reading makes sense, (e) connecting the information to your own experiences, (f) going back and rereading previous words or sentences, (g) evaluating the ideas, or (h) thinking about possible applications for this knowledge. These are all examples of cognitive operations. A cognitive operation is an act of thinking that operates on or engages with mental content in some form.

Figure 14.1 lists some of the cognitive operations used by effective readers (Brown, Palinscar, & Armbruster, 2013; Learned, Stockdill, & Moje, 2013; Lipson & Wixon, 2009, Tompkins, 2011). The specific ones used are dependent on the purpose for reading and content of what is read (Kucer, 2014). To enhance students’ ability to create meaning with print we must develop their ability to use these cognitive operations in the context of authentic reading situations (Almasi, Palmer, Madden, & Hart, 2011; Block & Lacina, 2009; Cartwright, 2015; Dole, Nokes, & Drits, 2009; Martin & Duke, 2011).

Too often the instruction and interventions used with students who are struggling readers focuses only on low-level skills (Allington & McGill-Franzen, 2017). This makes it high unlikely that they will develop the cognitive operations necessary to create meaning with print. The intervention activities described in this chapter all focus on developing cognitive processes related to effective comprehension.

TEACH THE PROCESS TO DEVELOP THE SKILL

As stated in Chapter 2, reading interventions should build on effective classroom instruction. However, comprehension tends to be severely under-taught in most classrooms (Allington & McGill-Franzen, 2017). The “comprehension” worksheets included with most basal reading programs do very little (if anything) to enhance students’ ability to create meaning with print. In fact, a more appropriate term for these worksheets might be “remembering” worksheets, or “go-back-and-find-details” worksheets, or “show-the-teacher-you-have-read-the-book” worksheets. There is a better way.

Comprehension Strategy vs. Comprehension Skill

This is a good place to differentiate between a comprehension strategy (more precisely defined as a study skill strategy), and a comprehension skill.

Comprehension strategies. As described in Chapter 5, a strategy is a cognitive process or set of steps that one consciously applies to a situation for a specific purpose. A comprehension strategy then would be a set of steps that one consciously applies before, during, or after reading for the express purpose of enhancing comprehension. When reading expository text, especially if the text is difficult or the content unfamiliar, most of us must consciously applying some sort of strategy to enable us to understand what we are reading.

A more precise term for comprehension strategies would be ‘study skill strategies’. These are used with expository text, the purpose of which is to understand or to construct knowledge. However, the purpose for reading narrative text is quite different. Here the purpose is to read and enjoy the story. Since the purposes for reading are quite different, it follows that the approaches to reading the two types of texts different. Study skill strategies should be used with expository text, not narrative text. Using a study skill strategy with narrative text would be like going to a movie with a friend and afterward, demanding that the friend identify the main idea, and supporting details.

Comprehension skills. A skill in this context, is a cognitive process that has become automated such that you have very little (if any) conscious awareness of it. A comprehension skill then would be a cognitive process that is automatically engaged during the act of reading. The purpose of an intervention for reading comprehension is to automatize students’ use of one or more of the cognitive operations identified in Figure 14.1 during the act of reading. Thus, we teach the various cognitive operations, not so that students can demonstrate mastery of them; rather, we teach the process (cognitive operation) to develop the skill (automaticity).

This is not to imply that study skill strategies should be ignored. These should be explicitly taught to all students every year starting in grade 3. Methods for instruction and types of study skill strategies are described in other publications (Johnson, 2016). However, the focus here is on comprehension skills.

How you Teach the Process

Comprehension can be improved by teaching the cognitive processes in Figure 14.1 using the elements of effective skills instruction (Allington & McGill-Franzen, 2017, Johnson, 2000). Here the teacher explains and models the cognitive operation, takes students through the cognitive operation using guided practice with a gradual release of responsibility, and then uses independent practice to enable students to practice the skill (see Figure 14.2). When a cognitive operation is introduced in an intervention, these elements should be used to teach it.